Maynard Dixon

1875-1946

At last,

At last,

I shall give myself to the desert again,

that I, in it’s golden dust,

may be blown from a barren peak,

broadcast over the sun-lands.

If you should desire some news from me,

go ask the little horned toad

whose home is the dust,

or seek it among the fragrant sage,

or question the mountain juniper,

and, by their silence,

they will truly inform you.

~ Maynard Dixon

There has been a resurgence of interest in Maynard Dixon’s life and works. A retrospective exhibition of his art as well as educational tours of “Maynard Dixon Country” have introduced a wider public to this essential Western artist. Why does Maynard Dixon’s fame continue to spread over half a century after his death?

Almost everyone recognizes his superb artistic skill and honest vision. Some credit his deep understanding of the West. But maybe more than anything else, it is his uniquely modern style, one that gave the West a new language of expression that makes Maynard Dixon’s work so exciting.

Dixon was born to a ranching family in 1875 in Fresno, California. Much has been spoken and written about his early years – his sending of early drawings to Frederic Remington (with encouragement received in reply) and his introduction to academic training under Arthur Mathews at the California School of Design in San Francisco. Suffice to say he had tremendous natural artistic talent and decided at an early age to become an illustrator of the Old West.

Great illustrators were plentiful around the turn of the century yet Dixon obtained work from the Overland Monthly and several San Francisco newspapers. In 1900 Dixon visited Arizona and New Mexico. This was the start of his lifelong passion for roaming the West. The next year he accompanied artist Edward Borein on a horseback trip through several Western states. In California, he illustrated books and magazines with Western themes. Some of his most memorable work from these early years appeared in Clarence Mulford’s books about Hopalong Cassidy.

Dixon developed his own unique style during this early period, and Western themes became a trademark for him. He spent a good deal of time with Xavier Martinez, whom he had met at the California School of Design. Martinez, a Tonalist painter of the first order, had known the famous American painter James McNeill Whistler while in Paris. That acquaintance gave Dixon his first step toward modernism.

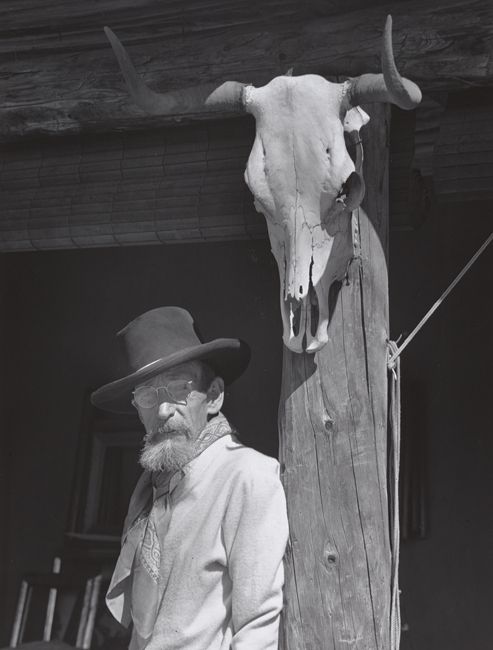

In San Francisco, Dixon was considered a colorful character with a good sense of humor. He often dressed like a cowboy and seemed determined to impart a Western style, most often in the form of a black Stetson, boots and a bolo tie.

A remarkable transition occurred in Dixon’s art in 1915. That was the year of the Panama Pacific International Exposition, and the entire West Coast art community was exposed to the New Art. Room after room of colorful artwork provided juicy examples of Fauvism, Impressionism, and the move toward abstraction by French artists as well as East Coast painters, too. With this exposure to Impressionism, California painters began shifting to the new styles of art. Dixon’s pursuant post-Impressionist approach revealed his search for his own answer to modernism.

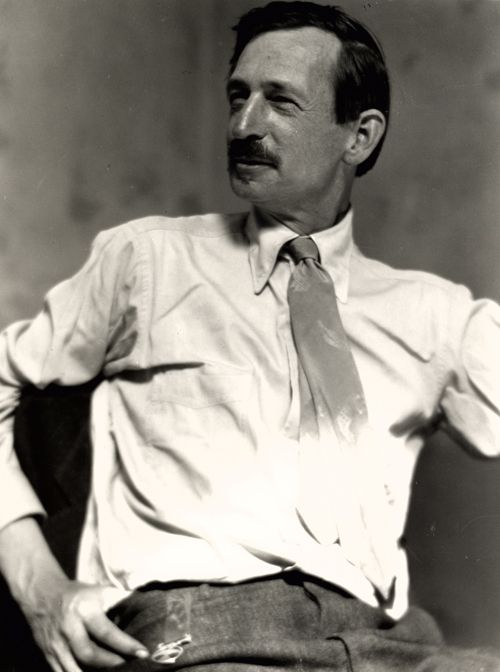

In 1919, Dixon met a portrait photographer, Dorothea Lange, who came from the East seeking a new life in San Francisco. She had a new vision, and the simple compositions she made in black-and-white were modernist and abstract. The two married in 1920.

Dixon continued his travels and accompanied Lange to Nevada and later to Arizona. His paintings had changed dramatically in the period following his marriage. To convey his message he no longer relied on paint but on powerful and simple compositions. In 1921, at the age of 46, Dixon created some 60 paintings while discovering the power of the low horizon and marching cloud formations.

From 1922 through 1927, Dixon painted 100 works. His shapes became stylized and defined, and he was extremely confident in his emerging modern style. He had begun to deliver strong messages with the utmost simplification. Together with his wife and two young sons, Dixon scoured the West in search of inspiration, visiting northern New Mexico around Taos and present-day Zion National Park in Utah.

From 1922 through 1927, Dixon painted 100 works. His shapes became stylized and defined, and he was extremely confident in his emerging modern style. He had begun to deliver strong messages with the utmost simplification. Together with his wife and two young sons, Dixon scoured the West in search of inspiration, visiting northern New Mexico around Taos and present-day Zion National Park in Utah.

During the Great Depression, Dixon took a slight turn at the crossroads with a series of social realism canvasses depicting the prevailing politics and the violence of maritime strikes along the waterfront. Simultaneously Lange captured on film memorable images of migrant workers and other aspects of the Depression. In 1933 Dixon and family spent the summer in Zion National Park and Mt. Carmel, Utah.

Dixon and Lange divorced in 1935. Two years later he married prominent San Francisco muralist Edith Hamlin. The couple left San Francisco two years later for Southern Utah, the source of some of Dixon’s greatest art. He had returned to inspiration of the land where the spirit moved him and gave him the peace he sought.

In 1939, the couple built a summerhouse in Mount Carmel, Utah, where Dixon found new friends and became reacquainted with the earth. He lived near the cottonwood trees along an old irrigation ditch and took short hikes to a plateau where he loved the quiet. Dixon spent winter months in Tucson, where the couple also had a home and studio.

Dixon continued to create masterpieces – simple but powerful compositions in which non-essential elements were distilled or eliminated. In 1946, this master of American modernism passed away in Tucson, and his ashes were then taken to Mt. Carmel and buried on the hillside.

Maynard Dixon’s art had evolved through the tumultuous years of modernism’s onset, and he had incorporated its aesthetic while continuing to focus on Western subjects. His superlative skills as an illustrator were brought into the mix, and he emerged with his own incomparable images in his own style. These images of people and places reflect those Dixon saw in his travels and his sojourns in and around the West, characterized by the qualities of clarity, honesty, and of course, beauty.

Is it any wonder Maynard Dixon’s works continue to gain new admirers and inspire us as no other? Wherever the wide-open spaces of the West, its canyons, mesas, cottonwoods, clouds, sagebrush, and people, strike a chord in the heart, Maynard Dixon’s art will be honored.

Also, we are very happy to report that the Maynard Dixon home and studio in Mt. Carmel Utah has officially been placed on the National Register of Historic Places. This means that a marker will be erected this year along Historic Highway 89 marking the place where Dixon spent the last years of his life and the area where Edith Hamlin spread his ashes after his death and placed a marker on the hillside.